No New Yorker’s life is complete without a MetroCard slipped into their wallet. For $2.75, it’ll get you from Brooklyn to the Bronx, and everywhere in between. But the lifespan of the MetroCard is perhaps shorter than you might think–the flimsy plastic card, complete with the Automated Fare Collection turnstiles, only became an everyday part of subway commuting in 1993. And in recent years, all signs point to the card becoming extinct. The testing phase of a mobile device scanning and payment system began this fall with plans to roll out a fully cardless system by 2020. And so in honor of the MetroCard’s brief lifespan as an essential commuter tool, 6sqft is delving into its history, iconic design, and the frustrations that come when that swipe just doesn’t go through.

Amazingly, the predecessor to the MetroCard, the subway token, wasn’t officially discontinued until 2003. The coin-based ticket has a long history with the NYC subway. When the system first opened in 1904, it only cost five cents to get on a train–you just inserted a nickel to catch a ride. In 1948, the fare was raised to ten cents, so NYC’s Transit Authority re-outfitted the turnstiles to accept dimes. But when the fare went up to fifteen cents, the city faced a problem without a fifteen cent coin. Hence, the token was invented in 1953, and it went through five different iterations before it was ultimately discontinued.

The MetroCard was a huge gamble when it was first introduced in the early 1990s to replace the token, according to Gizmodo. Tokens had worked well because the MTA could use the same turnstile technology for decades on end, plus a token system could easily accommodate fair increases. But a computerized system was certainly appealing to the MTA, as it could provide real-time data regarding the exact location, and time, every commuter entered the station or boarded a bus.

The MetroCard, then, was introduced in 1993, and the rest is history. It was a huge shift for transit users at the time. Jack Lusk, a senior vice president with the MTA, told the New York Times in 1993 that “this is going to be the biggest change in the culture of the subways since World War II, when the system was unified… we think the technology is working just fine. But it may take riders some getting used to.” It would take until May 14th, 1997, for the entire bus and subway system to get outfitted for the MetroCard.

Cubic Transportation Systems designed the magnetic-stripped, blue-and-yellow card to respond to a swipe-based system. Here’s how it works: each MetroCard is assigned a unique, permanent ten-digit serial number when it is manufactured. The value is stored magnetically on the card itself, while the card’s transaction history is held centrally in the Automated Fare Collection (AFC) Database. After that card is loaded with money and swiped through a turnstile, the value of the card is read, the new value is written, the rider goes through and the central database is updated with the new transaction.

The benefits of the new technology–and cards that could be loaded with data–were obvious. MTA had data on purchases and ridership. Payment data was kept on the card, meaning the value of the card would adjust with each swipe. Different types of MetroCards could be issued to students, seniors, or workers like police and firemen with specified data. Unlike a token, weekly and monthly cards provided an unlimited number of rides during a fixed period of time. Cards also allowed for free transfers between the bus and subway–a program originally billed as “MetroCard Gold.”

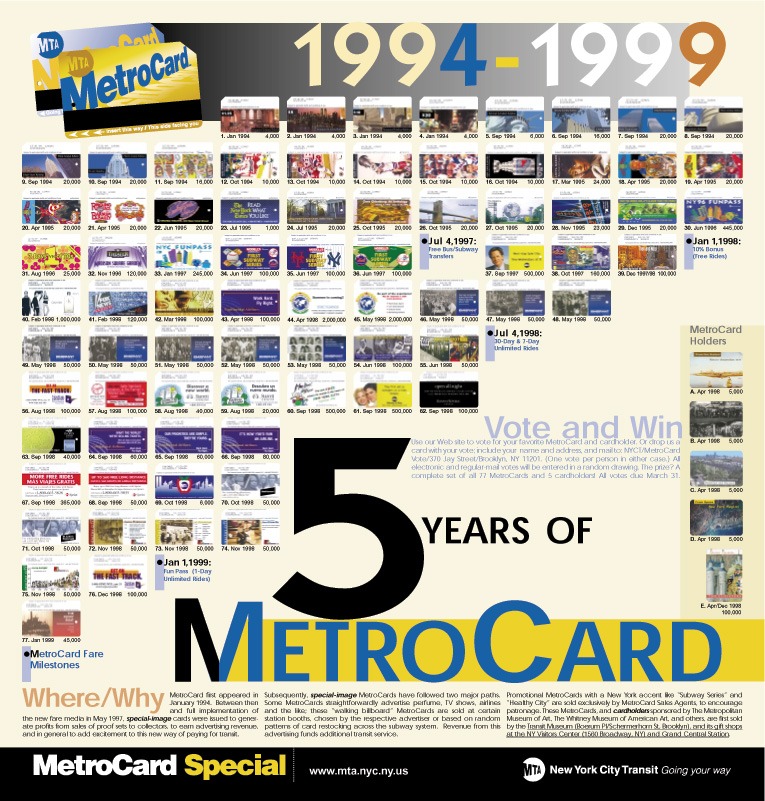

Another early perk to the MetroCard? The MTA got the opportunity in selling advertising. This begins in 1995, with ads appearing on the backs of cards as well as different commemorative designs coming out over the years.

In 2012, the MTA began offering up both the front and back of MetroCards to advertisers. Within a few years–and into present day–it’s become common to receive an ad-covered MetroCard. Some even became collectible, like the Supreme-branded cards released earlier this year.

But the difficulty of using the card–and swiping it just so–has persisted. The 1993 Timesreport detailed a new MetroCard user who “needed to swipe his ‘Metrocard’ through the electronic reader on a turnstile three times before the machine would let him pass and board the F train.” Not much has changed since then.

This October, the MTA took a significant step toward a more seamless and modern way for riders to pay their fares. And by late next year, New Yorkers will be able to commute by waving cellphones or certain kinds of credit or debit cards at the turnstiles in the subway or the fareboxes on buses. (The system is being adapted from the one used on the London Underground.) According to the MTA, new electronic readers will be installed in 500 subway turnstiles and 600 buses beginning in late 2018, with the ultimate goal of going into the entire transit system by late 2020.

Joe Lhota, chairman of the MTA, recently told the New York Times, “It’s the next step in bringing us into the 21st century, which we need to do. It’s going to be transformative.” It sounds a lot like the MTA back in 1993. But this time, we’re going to be saying goodbye to the MetroCard for good.