In mid-20th century America–particularly in New York City–a roaring economy emboldened by our ascendant international stature filled many a scholar of public infrastructure with eagerness to execute grand ideas. This proposal to drain the East River to alleviate traffic congestion, for example.

Another ambitious but unrealized plan–one that would make it a lot easier to get to New Jersey–was championed in 1934 by one Norman Sper, “noted publicist and engineering scholar,” as detailed in Modern Mechanix magazine. In order to address New York City’s traffic and housing problems, Sper proposed that if we were to “plug up the Hudson river at both ends of Manhattan,” and dam and fill the resulting space, the ten square miles gained would provide land to build thousands of additional buildings, as well as to add streets and twice the number of avenues to alleviate an increasingly menacing gridlock.

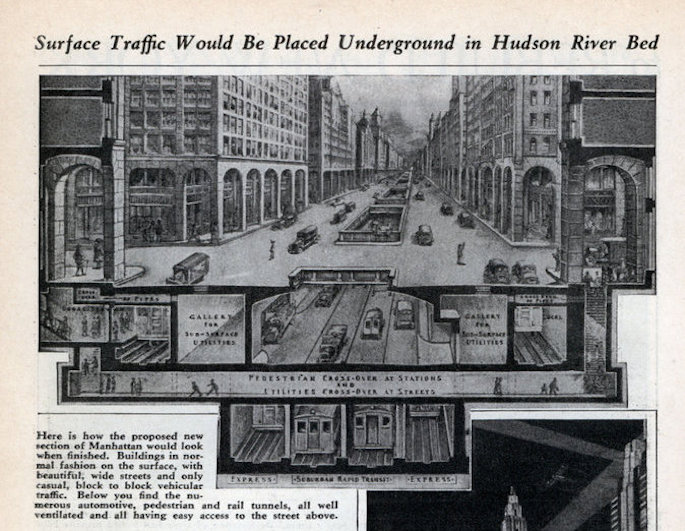

Eager to get at the benefits of the ambitious undertaking, Sper suggested not waiting until the project was complete (because we all know how that goes) to begin working on “underground improvements” like “tunnels, conduits, mail and automobile tubes, and other subterranean passages indispensable to comfort in the biggest city in the universe,” while in the process filling in the watery basin. Then a secondary fill would shore up the new turf to a level within 25 feet of the Manhattan street level.

Above ground would be “fresh air, sunshine and beauty,” and below would be an unprecedented subterranean network to which we’d confine all heavy trucking (ok, can we maybe revisit this just a little?)–and as a bonus would serve as a giant bomb shelter in case of a gas attack. The cost: $1 billion.

At the time, civic projects were only beginning to be seen in hundreds of millions: “This single project would cost within approximately one-thirtieth of the total of the public debt of the United States government as it now stands.” For comparison, the first phase of the Second Avenue Subway alone is projected to cost $4.45 billion; the U.S. public debt in 2016 is $13.62 trillion.

Sper enthusiastically pointed to the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges and the Panama Canal as examples of the triumph of our human will, which was something that critics of the day had a tough time arguing with, as the article proclaims, “Engineers uniformly agree that there are very few problems which can successfully defy the determination of civilization to conquer.”

In discussions of the plan, engineers justified the necessary government financial outlay by pointing to a subsequent immediate income of “almost unbelievable dimensions” from, for example, selling the reclaimed land or leasing it for 99-year periods to developers who’d then reap huge sales or rental profits (which means times haven’t changed so much).

The article quotes several fine engineering minds of the day, who weigh in with caveats aplenty that it’s certainly well within the realm of the possible. One notable take on the project comes from “engineering wizard” Jesse W. Reno; though he’s aware of the “almost insurmountable impediments” that appear when assessing the possibilities, “…there is an old saying that if you have money enough, everything else merely resolves itself into finding something to do with it,” a sentiment with which any 21st century wizard might concur.